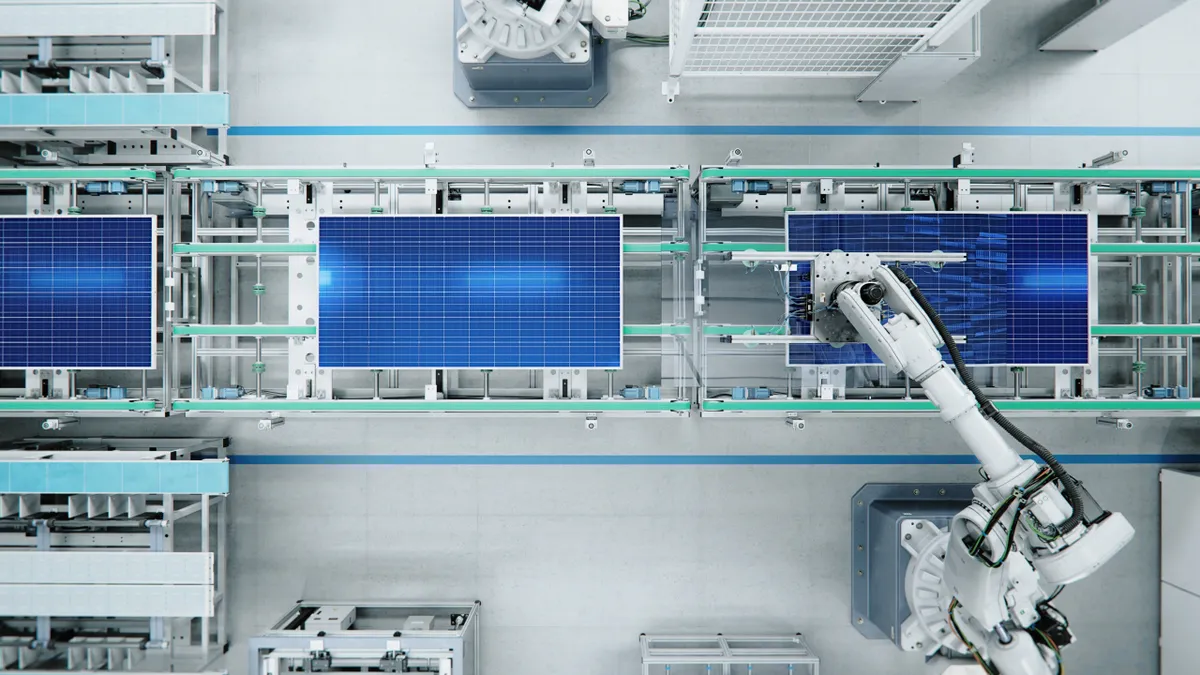

South Korea is leading the pack when it comes to integrating robotics on the shopfloor, using more robots per factory worker than the U.S., Germany, China or Japan.

For the U.S. to become a leader in automation, it will require a federal effort including a central government robotics office, tax incentives and expanded workforce training programs, among other actions — or so says the Association for Advancing Automation (A3), which recently announced an ambitious proposal for putting the U.S. on top.

Though the importance of a clear strategy is apparent to many industry professionals, the plan’s timing, interplay with the current administration’s manufacturing priorities and nature of its execution remain uncertain.

Supply chain dependencies

One of the major pain points addressed by A3’s proposal is the lack of a central federal office centered on robotics.

“[If] you want to talk about robotics to the U.S. government, you need to go to the National Science Foundation, you need to go to the Department of Defense. You don't know where to go,” said A3 President Jeff Burnstein.

This decentralization results in a constellation of challenges felt across the industry but not easily resolved. One of the most significant of these issues is a lack of a domestic supply chain for parts used to build robots, including actuators, sensors, and other specialized components, said Carnegie Mellon University robotics professor Martial Hebert.

“If you look at other countries like China, you can get those middle layer components very quickly and very cheaply. That [supply chain] does not exist in the U.S., or at least not nearly at that scale,” Hebert said.

That vacuum perpetuates a cycle wherein the production base remains small, leading to less usage and further demotivating the creation of a production base, Hebert said.

“Part of the strategy is to break that cycle and to put mechanisms in place to facilitate that,” Hebert said. “Once we have more substantial infrastructure, [we’ll] have the opportunity to experiment with those systems and to innovate with new ideas.”

The importance of federal intervention

Multiple experts agree that federal intervention is necessary to boost the U.S. as a leader in the robotics race.

China stands as an example of a nation whose national interest in robotics has paid off. Backed by huge investment and government buy-in, the country now has more automated factories than Japan, Germany and the U.S.

The U.S. too, however, has clear examples that point to symbiosis between the manufacturing industry and government.

The 2022 CHIPS and Science Act provided nearly $53 billion in funding to boost the manufacturing and research of semiconductors in the U.S. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, the landmark law has resulted in 16 new semiconductor manufacturing facilities as of August 2024 and is “expected to create over 115,000 manufacturing and construction jobs.”

The CHIPS’ Act's future, however, remains in flux under the Trump administration, which has been more critical of using direct subsidies to grow domestic manufacturing.

This isn’t the first such example in U.S. history — the computer numerical control equipment industry experienced huge growth in the 1950s thanks to federal involvement.

According to Massachusetts Institute of Technology science and technology policy lecturer William Boone Bonvillian: “The Defense Department decided it had to have this level of precision machining for all of its missile and rocket programs. The department, by requiring its defense contractors to adopt this technology then using the Defense Production Act to assist them, almost single-handedly created the whole CNC machining industry.”

Past successes underscore the need for further federal leadership to grow specific manufacturing technologies, Bonvillian said.

“The standing of the U.S. in AI and robotics, if you trace it back, is due in large part to national initiatives around both areas. In other words, it won't happen just by market forces,” Hebert said.

What’s less clear from such a strategy is how it might interact with the current Trump administration’s manufacturing initiatives, which prioritize domestic manufacturing, tariffs to support domestic industries and workforce training, among other measures.

“There's an underlying political challenge, which is that the Trump administration has embarked on a trade tariff policy and has not really embarked on what we could call an industrial innovation policy,” Bonvillian said. “They're tackling manufacturing problems from a trade perspective.”

Centering robotics, with all their productivity-boosting capabilities, could actually help in the current administration’s efforts to grow domestic manufacturing output, Burnstein said.

In the event a national robotics office were established, it might benefit from uniting with other advanced manufacturing technology groups.

That model could follow in the coattails of Manufacturing USA — a network of institutes focused on reducing the gap between research and commercialization across several advanced manufacturing technologies, according to Bonvillian.

A similar kind of partnership could bolster support for a national robotics office and simultaneously give it the resources it needs to execute on the six priorities laid out in A3’s strategy, Bonvillian said, including not only the central robotics office and commission, but offering tax incentives, promoting government use of robotics, expanding workforce training, funding R&D and updating industry standards.

It could also offer support on education programming, economic development and industry leadership, Bonvillian added.

“In order to make progress on a lot of these issues, you're going to have to have a coalition involved,” Bonvillian said. “I think that a coalition kind of model is the right approach, and that's exactly what the manufacturing institutes attempted to do.”